Alex Tang

Articles

- General

- Theology

- Paul

- Karl Barth

- Spiritual Formation

- Christian Education

- Spiritual Direction

- Spirituality

- Worship

- Church

- Parenting

- Medical

- Bioethics

- Books Reviews

- Videos

- Audios

- PhD dissertation

Spiritual writing

- e-Reflections

- Devotions

- The Abba Ah Beng Chronicles

- Bible Lands

- Conversations with my granddaughter

- Conversations with my grandson

- Poems

- Prayers

Nurturing/ Teaching Courses

- Sermons

- Beginning Christian Life Studies

- The Apostles' Creed

- Child Health and Nutrition

- Biomedical Ethics

- Spiritual Direction

- Spiritual Formation

- Spiritual formation communities

- Retreats

Engaging Culture

- Bioethics

- Glocalisation

- Books and Reading

- A Writing Life

- Star Trek

- Science Fiction

- Comics

- Movies

- Gaming

- Photography

- The End is Near

My Notebook

My blogs

- Spiritual Formation on the Run

- Random Musings from a Doctor's Chair

- Random Sermons from a Doctor's Chair

- Random Writings from a Doctor's Chair

- Random Spirituality from a Doctor's Chair

Books Recommendation

---------------------

Medical Students /Paediatric notes

END-OF-LIFE PLANNING AND EUTHANASIA

Jonathan Yao, East Asia School of Theology (EAST), Singapore

I. Introduction

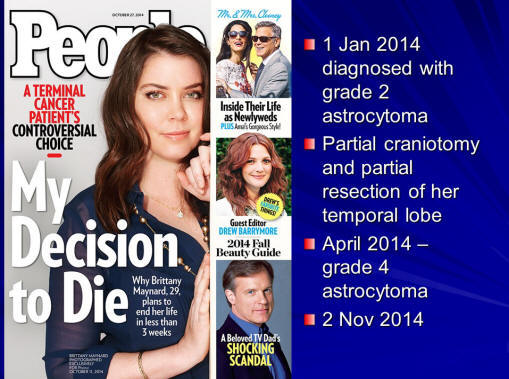

Since everyone will face death sooner or later, knowing and addressing end-of-life issues is beneficial to individuals, to the society as community is affected through the dying or death of individuals, and to the Church. The latter not only can exert moral and spiritual influence on such issues but it also “has a biblical mandate to care for the sick, the poor and the lonely,” as noted by Alex Tang who is a Senior Consultant Paediatrician, Adjunct Faculty on Biomedical Ethics, and Church Elder.[1] In ministering to the whole person in the Church’s disciple-making process and the Christian impact it can have on society where these disciples are located, important bioethical issues such as those relating to life and death have to be adequately addressed so that the “salt and light” of believers can be made manifest.[2]

This paper seeks to address selected end-of-life ethical and practical issues in the immediate context of Singapore culture. A brief discussion of euthanasia to define and understand related terms is then followed by a survey of biblical principles to discern its validity or otherwise. In applying these principles to end-of-life planning, practical guidelines will then be explored.

II. Euthanasia Explained

Euthanasia literally means “good death” in the original Greek (eu meaning “well” or “good,” and thanatos meaning “death”). According to Keith Essex, Professor of Bible Exposition, in its original context, the focus is on the manner of dying, as in the person meeting death having a peace of mind with minimal physical or mental pain.[3] Francis Beckwith and Norman Geisler, both theologians and apologists, explains that in current use, it means “mercy killing” and “is the intentional taking of a human life for some [supposedly] good purpose, such as to relieve suffering or pain.”[4]

The following seeks to define common terms as they relate to euthanasia:

Active Euthanasia is doing something positive in order to bring about the death of another who is suffering (through a lethal injection, for example).

Passive Euthanasia is intentionally causing death of another by not providing necessary and ordinary medical care or sustenance and hydration (by starving or dehydrating a patient, for example).

Voluntary Euthanasia occurs when a competent person requests death or with his or her consent and the person’s desire is met.

Involuntary Euthanasia occurs when a person did not explicitly gave his or her consent, but was put to death anyway. It includes someone being intentionally put to death against his or her wishes.

Non-voluntary euthanasia occurs when the person who was put to death lacked the capacity to know or express his or her desires (an infant or a person with severe brain damage or dementia, for example).[5],[6],[7]

Note that withdrawal of medical treatment from terminal patients is not passive euthanasia because it is not a form of passive suicide. Robert Wennberg, a philosophical ethics scholar, explicates passive suicide (and passive euthanasia) as when a patient “(a) intentionally ends his life (b) by a medical omission (c) when death is not imminent and (d) when it is done to relieve himself of suffering.” [8] The intent is the key difference between passive euthanasia (suicide) and “the withholding or withdrawing of life-preserving medical treatments because the treatments are not effective and offers no further benefits.”[9]-[10] The former causes or hastens death, the latter allows the person to die naturally.

It is helpful to understand the principle or “doctrine” of double effect. This refers to an action that has two effects, one desired and the other unwanted. An application of the double effect doctrine is when we are obliged both to preserve life and to relieve pain.[11]

In summary, active euthanasia, passive euthanasia, and voluntary euthanasia collectively is suicide, while involuntary and non-voluntary euthanasia is homicide. The withdrawal of ineffectual medical treatments, including life-preserving medical treatments, from terminal patients is not passive euthanasia.

III. Is Euthanasia A Biblically Acceptable End-of-Life Option?

In assessing the viability of euthanasia as an option for end-of-life planning, Bible-believing Christians would sought out Scripture as the primary basis for Christian thinking and action (2 Tim 3:16-17). This does not preclude other arguments made on this issue, but ultimate decisions must be aligned to and submitted under God’s Word.

A. Personhood And The Sanctity Of Human Life

The bible clearly states that every human person is made in the image of God (Gen 1:26-27; 5:1). Every individual thus has a God-given dignity that cannot be lost regardless of his physical or mental state. Whoever has the DNA of human beings is a person (also known as the species principle). This is greatly contrasted with the sociological and developmental view of personhood.[12]

Human life is sacred precisely because every person is made in God’s image. Theologians John Feinberg and Paul Feinberg stated that life is so valuable that one could only end it if an exceptional reason dictate such a deeply serious action. The bible listed such exceptions like killing within the context of a just war, for self-defence, and as capital punishment (see section III. B. below).[13]

Life is also sacred because God alone, from whom all life derives, has the authority in matters of life and death. Feinberg remonstrates that to treat life lightly then is an act of ingratitude and we presumptuously think we own our life, when in fact God gave it and sustains it. The sanctity of life is strongly upheld by biblical commands against life-taking. Killing is explicitly condemned in both the Old Testament and New Testament regardless whether it is accidental or intentional (see section III. B. below).[14]

B. Homicide Is Clearly Condemned By Scripture

The sixth of the Ten Commandments clearly prohibits the killing of life (Exo 20:23; Deu 5:17). Essex noted that whether one is killed accidentally (“manslaughter” in legal term) or intentionally (“murder” in legal term), the killer would face punishment albeit with different severity.[15] He then quoted the Old Testament scholar Gordon Wensham on the significance of the sixth commandment:

This law reaffirms in judicial fashion the sanctity of human life (cf. Gen. 9:5-6; Ex. 20:13). The commandment simply says ‘Thou shall not kill.’ The Hebrew ‘kill’ is used in this law both of murder and manslaughter (16, 25). Both incur blood guilt and pollute the land, and both require atonement: murder by the execution of the murderer and manslaughter through the natural demise of the high priest.[16]

The Israelite knew that life came from God (Gen 2:7) and therefore he must do all that he can humanly to preserve it and to avoid destroying it. Such a commitment to prevent accidental death is illustrated by a law in Deuteronomy 22:8, “When you build a new house, you shall make a parapet for your roof, that you may not bring bloodguilt on your house if anyone falls from it” (NASB).

In the Old Testament, God allowed exceptions to certain killings which will not incur punishments.[17] However, these exceptions are clearly demarcated and even then moderation was required. Therefore, one should not seek to increase these exceptions but instead follow the spirit of the commandment to preserve lives.

Essex emphasized that in the New Testament, the sixth commandment is mentioned extensively (Matt 19:18; Mark 10:19; Luke 18:20; Rom 13:9; Jas 2:11) and thus applicable to believers in Christ. Paul states in Romans 13:8-10 that by obeying all the commandments, the Christian shows love to others; thus true love is shown by preserving life and not by ending it.[18]

C. Suicide Is Implicitly Condemned In The Bible

Suicide, or the act of self-killing, is not directly addressed in scripture. Though there are five cases of suicide recorded in the Old Testament and one in the New Testament, these passages do not specifically condemn nor condone these actions. However, the condemnation against self-killing is inferred from the sixth commandment as it includes any form of killing or shortening the life of a person, in this case, himself or herself. [19]-[20]

Furthermore, followers of Christ are commanded to not only love others but to love themselves as well (Mat 22:39; Eph 5:28-29, 33). Suicide is an act of self-hate, not self-love. It conveys a low view of the worth of life, in this case one’s own. Therefore voluntary euthanasia is morally wrong because it is an act of disobedience against God shown by a rejection of His commandments.[21]

D. Martyrs, Jesus, And Intent

Is martyrdom a form of suicide? Furthermore, when Jesus said, “No one has taken it [my life] away from me, but I lay it down on my own initiative.” (Jn 10:18a, NASB), could it be understood as a form of suicide?

Wennberg maintains that “a suicide is someone who intends to die, either as a means…or as an end”.[22] Intent is, therefore, the decisive factor. For a martyr, the intent is to keep one’s faith and not renounce it while the unintended consequence is possibly death. Unintended does not mean uninformed. It is not considered a suicide for a soldier doing his duty to charge the enemy line while knowing he could lose his life. Such cases demonstrates the principle of double effect mentioned earlier. Therefore, martyrs who do not intent to die but would be willing to do so rather than deny their faith are not seen as committing suicide.

Based on the aforementioned John 10:18a, was Jesus’ death a form of suicide? According to Essex, the answer may be found in the deity of Christ. As the Son of God, Jesus has life in and of himself (John 1:4; 5:26) and unless he willingly gave it up, no man could take it from him. It is also clear that he was put to death by violent men (Acts 2:23; 3:14-15). Jesus was killed by others and not by himself.[23] Therefore, Jesus’ declaration in John 10 did not constitute a statement of suicide.

It is the opinion of the writer, therefore, that scripturally euthanasia is morally wrong as such action impugns the value of personhood, rejects the sovereignty of God, and violates His commands to preserve life, one’s own as well as others. In this paper, euthanasia precludes martyrdom, the death of Jesus, and Old Testament delimited exceptions as explained above.

IV. End-of-Life Planning And Care

As mentioned earlier, the mandate for the Church is the need to care for those who are in need, especially those who are dying and their families. At the same time, since those who are actually facing their own mortality may not be in a mental or emotional state to make major decisions that are literally life and death for themselves, it is desirable for them to address end-of-life issues through advance planning. It is proposed that these two goes hand-in-hand for a holistic approach toward a good death.[24]

John Dunlop, an internal medicine geriatrician, bioethicist, and church elder, lists the following attributes of a good death:

1) A good death is the natural trajectory of faith commitments made earlier in life.

2) A good death may require advance planning.

3) A good death has completed relationships including those that need reconciliation.

4) A good death comes after we cease clinging to the things and values of this world and increasingly embrace eternity.

5) A good death comes to the one whose spirit has been enriched by the difficulties of the end of life.

6) A good death will often come after a carefully considered decision not to pursue life-sustaining treatment.

7) A good death is peaceful, for the dying person knows that it will lead to resurrection and eternal life in God’s presence.[25]-[26]

It appears that the journey during the end-of-life phase is meant to be formational for the believer going through it. There appears to be four needs that are to be met arising from the above seven attributes: i) A need for advance planning (attribute 1); ii) A need for an informed decision on euthanasia and extra-ordinary life-sustaining treatment (attribute 6); iii) A need for an effective process to embrace faith, reconcile relationships, and face eternity (attributes 1, 3, 4); iv) A need for a formational mindset toward an enriched and peaceful journey to the end (attributes 5, 7).

The first two needs (i and ii) are inter-connected and may be dealt with as part of the advance planning (see section IV. B. below); it is noted that any advance decision may be tested again when actual end-of-life decisions are to be made though mitigated by the advance planning. The last two needs (iii and iv) are inter-connected as well because it not only involves the person’s agreement to move toward meeting those needs, but also the help of community of likeminded care givers (see section IV. A. below).

A. End-of-Life Teaching and Caring Ministry

The church can surely help prepare the way by its teaching ministry and practical caring ministry. The teaching component should take place as part of the educational ministry of church life which prepares every member to be both a potential informed care giver and an advance preparation for their own future end-of-life stage. The teaching should cover the spiritual need for continuance of the faith development process into the end-of-life phase: a life-long process of letting go of self and of the world to turn to the values and things of God and Heaven; and the need to keep short accounts with one another for strong heart-connected relationships. One does not need until near the end of one’s life to utter the important “four things”: I love you, thank you, I forgive you, and forgive me. The sense of completeness and closure is certainly a satisfying one.[27]

The end-of-life caring ministry is an intentional group of compassionate yet practical mature believers who see the caring and serving of those who are at the terminal stage as part of the spiritual formation process before these dear ones are ushered into God’s glory. The journey through sufferings infused with His shalom peace is an intensely personal experience on one hand and yet can be a blessedly communal process on the other. It should be a process accompanied by fellow saints “cheering” the person on with dignity. Across ethnic and religious lines, the common expressed caring need is for the extended familial engagement in the journey for which the church community can be a significant resource. The caring ministry extends to the dying and their family.[28]

While specific instruments to help with advance planning will be covered in the next section, it is noted that the exposure to these instruments should be included as part of the training curriculum in this section. Relevant medical and legal advice may be provided by competent professionals who are members of the church and/or invited to be part of the teaching team.

B. End-of-Life Advance Planning

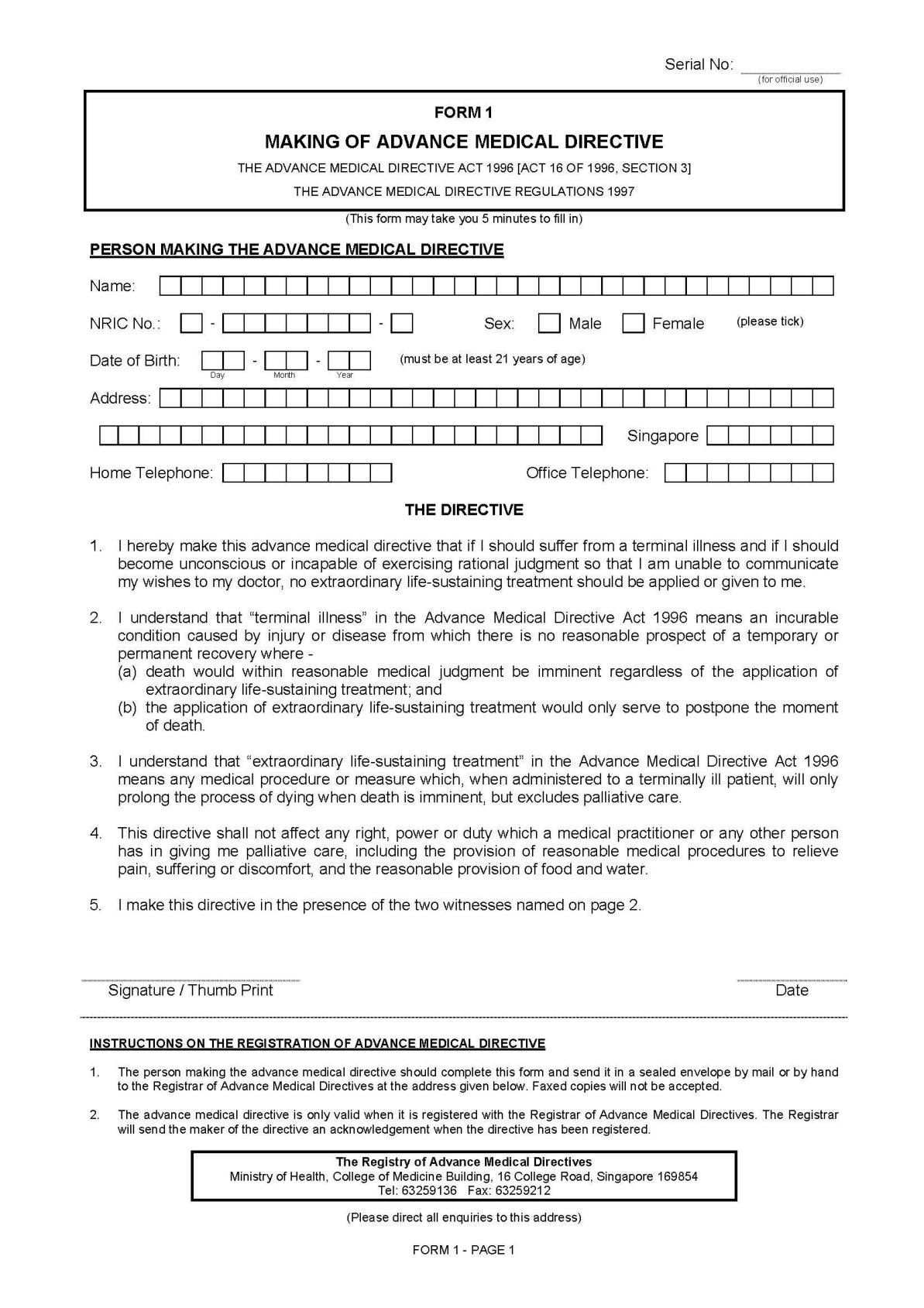

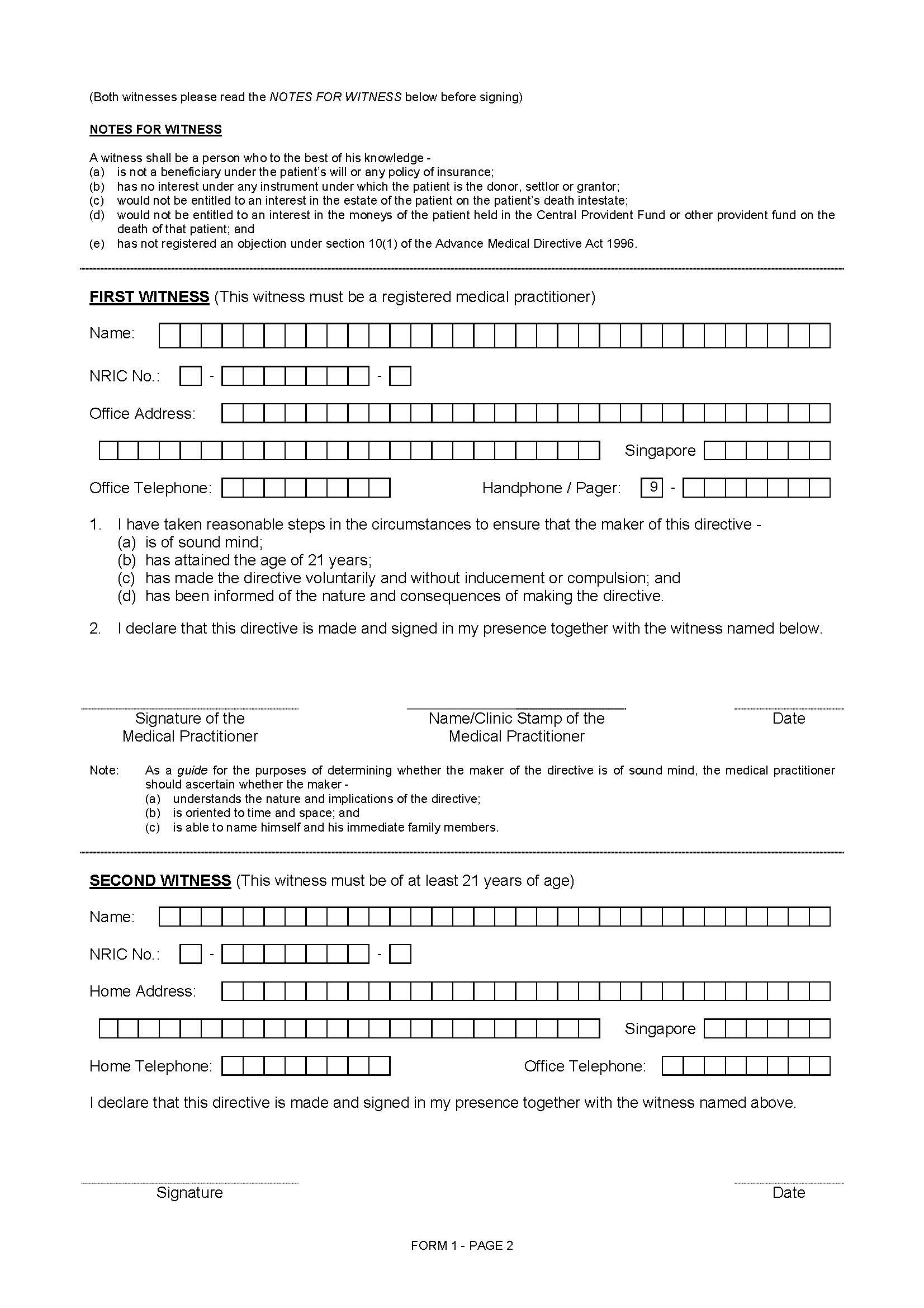

When it comes to advance planning for one’s future end-of-life decision making, there are two possible instruments to help in the process: the advance medical directive or AMD (also known as living will or anticipatory decisions), and the lasting power of attorney (also known as durable power of attorney).

1. Advance Medical Directive

In Singapore, the AMD “is a legal document that you sign in advance to inform the doctor treating you (in the event you become terminally ill and unconscious) that you do not want any extraordinary life-sustaining treatment to be used to prolong your life.”[29] Furthermore, the Advance Medical Directive Act 1996, Section 17, makes it clear that it does not “authorise an act that causes or accelerates death as distinct from an act that permits the dying process to take its natural course.” It does not “condone, authorise or approve abetment of suicide, mercy killing or euthanasia.”[30] Any person above 21 years or older and of sound mind may make an advance medical directive, but only in the prescribed statutory form (see Appendix A for facsimile of the form). The actual directive stated in the prescribed form is as follow:

1. I hereby make this advance medical directive that if I should suffer from a terminal illness and if I should become unconscious or incapable of exercising rational judgment so that I am unable to communicate my wishes to my doctor, no extraordinary life-sustaining treatment should be applied or given to me.

2. I understand that “terminal illness” in the Advance Medical Directive Act 1996 means an incurable condition caused by injury or disease from which there is no reasonable prospect of a temporary or permanent recovery where

(a) death would within reasonable medical judgment be imminent regardless of the application of extraordinary life-sustaining treatment; and

(b) the application of extraordinary life-sustaining treatment would only serve to postpone the moment of death.

3. I understand that “extraordinary life-sustaining treatment” in the Advance Medical Directive Act 1996 means any medical procedure or measure which, when administered to a terminally ill patient, will only prolong the process of dying when death is imminent, but excludes palliative care.

4. This directive shall not affect any right, power or duty which a medical practitioner or any other person has in giving me palliative care, including the provision of reasonable medical procedures to relieve pain, suffering or discomfort, and the reasonable provision of food and water.[31]

For the Singapore AMD, there is no flexibility in the wordings and therefore either one agrees to it or one does not. This is not a flexible “living will” that may be crafted to one’s own desire and are found in, say, the USA.[32] It is debatable whether a customized living will can be legally enforceable under common law rather than the statutory Advance Medical Directive Act in Singapore as there has not been any such cases brought before the court of law.[33]

Reading the above four-point directives of the prescribed form, it seems clear that it is not passive euthanasia (passive suicide) as the intent is not to cause or accelerate death through the withholding or withdrawal of treatment that will only prolong the process of dying for the terminally ill with imminent death. The directive forbids the withholding of palliative care which includes sustenance and hydration among other things. The phrase “reasonable provision of food and water,” however, may be seen as fluid and open to interpretation as to what is “reasonable provision” or otherwise.

It is the opinion of the writer of this paper that the Singapore AMD as it stands does not appear to contradict biblical injunctions against killing.

2. Lasting Power of Attorney

Lasting power of attorney is a legal instrument where a proxy is given power to “make decisions about initiating, foregoing, or withdrawing end-of-life medical procedures when patients can no longer state their wishes about such decisions.”[34] The main advantage of such instrument over the advance medical directive is the flexibility (as compared to AMD) that actual proxies are able to react to on one’s behalf when one is no longer able to do so.[35]

Singapore’s version of lasting power of attorney was provided for under the enactment of the Mental Capacity Act 2008. Due to the complexity of this instrument, the details are beyond the scope of this paper. While legal counsel should be sought on this matter, the church can help educate and expose members to such instruments.

The local church, through its community of members, can provide teaching and care and/or in conjunction with their network or denomination of churches. This ministry would cater to those who are or related to those in the end-of-life situation commonly aspiring for a “good death.” The compassionate yet practical impact of such a ministry may well go far beyond affected members to the extended family and thus the larger community with the love of Christ.

V. Conclusion

In current use, euthanasia means mercy killing and is the intentional taking of a human life for some supposedly good purpose, such as to relieve suffering or pain. Euthanasia is categorized as Active or Passive (means of death due to acts of commission or omission); Voluntary, Involuntary, or Non-voluntary (whether prior personal consent of death was given or otherwise before execution). Active euthanasia, passive euthanasia, and voluntary euthanasia collectively is suicide, while involuntary and non-voluntary euthanasia is homicide. Withdrawal of ineffectual medical treatments, including life-preserving medical treatments, from terminally-ill patients is not considered passive euthanasia.

Scripturally, euthanasia is morally wrong as actions resulting in homicide or suicide impugns the value of personhood, rejects the sovereignty of God, and violates His commands to preserve life, one’s own as well as others. In this paper, euthanasia precludes martyrdom, the death of Jesus, and Old Testament delimited exceptions.

The local church, through its community of members, can provide practical teaching and compassionate care and/or in conjunction with their network or denomination of churches. This ministry would cater to those who are or related to those in the end-of-life situation commonly aspiring for a “good death.” Advance planning is part of preparing for one’s end-of-life journey and ideally should be done when the person is healthy (e.g. Spiritual Formation, Advance Medical Directive, and Lasting Power of Attorney). The outreach impact of such a ministry may go far beyond affected members and touch the extended family and thus the larger community with the love of Christ.

[1] Alex Tang, A Good Day to Die: A Christian Perspective on Mercy Killing (Singapore: Genesis Books, 2005), 103.

[2] Bioethics Issue Group, “Bioethics: Obstacle or Opportunity for the Gospel?” In 2004 Forum Occasional Papers, ed. David Claydon, (Pattaya, Thailand: Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization, 2004), 17-21.

[3] Keith H. Essex, “Euthanasia,” Master’s Seminary Journal 11, no. 2 (2000): 200-1, http://www.tms.edu/tmsj/tmsj11j.pdf (accessed 19 Dec. 2014).

[4] Francis J. Beckwith and Norman L. Geisler, Matters of Life and Death: Calm Answers to Tough Questions about Abortion and Euthanasia (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1991), 131.

[5] National Council of Churches of Singapore, “Euthanasia,” Official Statement, 6 Nov. 2008, http://info.ncss.org.sg/joom837/index.php/m-statements/22-s10 (accessed 5 Dec. 2014).

[6] John S. Feinberg and Paul D. Feinberg, Ethics for a Brave New World, 2d ed. (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2010), 175-6, Kindle.

[7] While not listed above, direct euthanasia and indirect euthanasia denotes the role played by the person who dies when his life is taken: In direct euthanasia, the person himself carries out the action to cause death. In indirect euthanasia, someone else carries out the action. See Essex, 201; Feinberg, 176-7.

[8] Robert N. Wennberg, Terminal Choices: Euthanasia, Suicide, and the Right to Die (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), 108-56, http://books.google.com.sg/books?id=KeY0rJ2qStsC (accessed 1 Feb. 2015).

[9] Wennberg, Terminal Choices, 25.

[10] Alex Tang, “Issues at the End of Life: Part 1, Euthanasia or ‘mercy killing’,” class handouts, East Asia School of Theology, 3 Dec. 2014, 9. Also Tang’s A Good Day to Die, 13, state “A deliberate intervention to end life is always morally wrong and should remain unlawful. An omission may be an example of euthanasia (and therefore morally wrong) if its intention is solely to cause death. However, an omission would be a good example of good medical practice if its intention were, say, to maximise the quality of life remaining to the patient, or to respect the wishes of the patient and his family. The difference lies in the intention.” As quoted from Submission from the Christian Medical Fellowship to the Select Committee of the House of Lords on Medical Ethics cited in http://www.cmf.org.uk/home.htm

[11] Feinberg illustrates: “Imagine a terminally ill patient who won’t recover who is in terrible pain. Imagine also that there is medicine that, if given in large doses, will relieve the pain; unfortunately, it will also hasten the patient’s death. Proponents of double effect reasoning think that giving medicine to relieve the pain is morally acceptable, even though the medicine will also speed death. … So long as the one giving the medicine intends to relieve pain rather than hasten death, giving the medication is morally justified.” See Feinberg, 185.

[12] The recognition of personhood of human beings by virtue of his “membership in the species Homo Sapiens” is known as the species principle as opposed to the actuality principle and the potentiality principle. The actuality principle “holds that an individual possess a right to life only when that individual possess self-awareness and self-reflective intelligence. This view is notorious because of the group with no right to live will include fetus, infants and the irreversibly comatose.” The potentiality principle “endorse the concept that it is wrong to kill what will naturally and in due course develop into a person. The potential is taken into consideration.” Quotes are taken from Alex Tang’s “Issues at the Beginning of Life: Abortion,” class handouts, East Asia School of Theology, 1 Dec. 2014, 17. Also see Robert N. Wennberg, “The Right to Life: Three Theories,” in Readings in Christian Ethics (Book 2): Issues and Applications, eds. David K. Clark and Robert V. Rakestraw (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1995), 36-45, https://books.google.com.sg/books?id=GJbX_C-XLywC (accessed 20 Dec. 2014).

[13] Feinberg, Ethics for a Brave New World, 190.

[14] Ibid., 191-2.

[15] Essex, 205-6.

[16] Gordon J. Wenham, Numbers: An Introduction and Commentary, The Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries, ed. D. J. Wiseman (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1981), 238, as quoted in Essex, 206.

[17] Keith Essex explained the exceptions: “… there were certain killings allowed by God (Num 35:27, 30). The manslayer who did not obey the LORD by staying in the city of refuge and the murderer were under the judicial judgment of God and could be put to death without violating the sixth commandment. By expansion, all the crimes of the OT that the LORD said were punishable by death were allowable killings. Further, the LORD also commanded Israel to kill their enemies in battle when He directed them to go to war (Deut 7:2; 20:17). By implication, when invasions took place, warfare that was defensive in nature, with the resulting killing, was also allowed by God (Gen 14:2; Judg 11:4-6; 1 Sam 17:1; 2 Kgs 6:8).” See Essex, 206.

[18] Essex, 207.

[19] Ibid, 210-1. The suicides found in the bible are: Abimelech (Judg 9:54); Saul and his armour bearer (1 Sam 31:4-5); Ahithopel (2 Sam 17:23); Zimri (1 Kgs 16:18); Judas (Mat 27:5; Acts 1:18). In reference to how we should view such narratives, Essex said, “The biblical reader must consider the whole presentation made in order to draw proper conclusions. For example, Saul is presented as a king who was disobedient to the LORD (1 Sam 13:13-14; 15:1-31; 28:3-19); Saul’s death was a judgment from the LORD for his disobedience (1 Chron 10:13-14). Saul’s suicide was the pathetic act of a rebel against God, not the heroic final act of a faithful servant of the LORD.”

[20] Wennberg pointed out that the biblical silence on suicide may be due to the lack of such a need in the Hebrew community: “…the Jewish belief that life is a gift from God to be lived out under providentially ordained conditions was so strong that it produced a society in which suicide was never seriously considered as a moral possibility and therefore did not require an explicit moral prohibition. In any case, the biblical silence need not be interpreted as approval or even indifference; indeed, both the Jewish and Christian traditions…have in fact repudiated suicide finding it incompatible with their theological beliefs.” See Wennberg, Terminal Choices, 46.

[21] Feinberg, 205-6.

[22] Wennberg, Terminal Choices, 22.

[23] Essex, 210.

[24] John Dunlop: “The end of life is the time when the patient can come to closure with this life and bring completion to relationships, reconciliation with problems of the past, and a feeling of spiritual peace. Allowing for these activities contributes to a truly ‘good death.’” John T. Dunlop, “A Good Death,” Ethics & Medicine: An International Journal of Bioethics 23 no. 2 (2007). Reproduced as “A Good Death,” 20 Jul. 2007. End of Life. Deerfield, IL: The Centre for Bioethics and Human Dignity, Trinity International University, n.d. https://cbhd.org/content/good-death (accessed Dec. 2014).

[25] Ibid.

[26] John Dunlop’s seven attributes apparently seems to cover most of Karen Kehl’s twelve “Attributes of a Good Death” as well (correlations marked with “*”): “1. *Being in control; 2. Being comfortable; 3. *Sense of closure; 4. *Affirmation/value of dying person recognized; 5. *Trust in care providers; 6. *Recognition of impending death; 7. *Beliefs and values honoured; 8. *Burden minimized; 9. *Relationships optimized; 10. *Appropriateness of death; 11. *Leaving a legacy; 12. *Family care.” See Karen A. Kehl, “Moving Toward Peace: An Analysis of the Concept of Good Death,” American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 23, no. 4 (2006): 281-282.

[27] Dunlop adds, “There should be no discontinuity between the faith we live by and the faith we die by. Scripture teaches that Christ has defeated the enemy of death. … It is when we slowly loosen our grasp on this world and reach out for God that we prepare to die well.” He also quoted the “four things” from Ira Byock’s The Four Things that Matter Most, Free Press, 2004.

[28] It is noted that John Dunlop’s end-of-life spiritual formation process does seem to address at least three of the five domains (no. 2, 3, 5) of quality end-of-life care listed by Deborah Volker based on study by Singer, Martin, and Kelner: “1. Receiving adequate pain control; 2. Avoiding inappropriate prolongation of the dying process; 3. Achieving a sense of control; 4. Relieving burden on loved ones; and 5. Strengthening relationships with loved ones.” Deborah L. Volker, “Control and End-of-Life Care: Does Ethnicity Matter?” American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 22, no. 6 (2005): 443.

[29] Ministry of Health, “Advance Medical Directive Act,” Legislation And Guidelines (Singapore: Ministry of Health, 2014), https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/legislation/

legislation_and_guidelines/advance_medical_directiveact.html (accessed 16 Dec. 2014).

[30] Legislative Division, “Advance Medical Directive Act (Chapter 4A),” Singapore Statutes Online (Singapore: Attorney-General’s Chambers, 2014) http://statutes.agc.gov.sg/aol/search/display/ view.w3p;page=0;query=DocId%3Ac3137d32-215d-4bd1-a935-fc4770fc5850%20Depth%3A0%20Status%3Ainforce;rec=0 (accessed 22 Dec. 2014).

[31] See Appendix A for the facsimile of the form. Ministry of Health, “Form 1: Making of Advance Medical Directive,” Forms (Singapore: Ministry of Health, 2014) https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/dam/

moh_web/Forms/FORM1AMD%28270905%29.pdf (accessed 16 Dec. 2014).

[32] For a description of living wills in the US, see Feinberg, 159.

[33] Terry Kaan, “Shifting Landscapes: Law and the End of Life in Singapore,” Singapore's Ageing Population: Managing Healthcare and End-of-Life Decisions, ed. Chan Wing Cheong, 157, Routledge Contemporary Southeast Asia Series (New York: Routledge, 2011) https://books.google.com.sg/books?id=5GarAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA137 (accessed 16 Dec. 2014).

[34] Feinberg, 159.

[35] Feinberg gave the following reasons on the advantages of lasting power of attorney over the advance medical directive: “First, you get to name the person you want to have making the decision if a medical crisis arises. … Second, in this document you can state as many guidelines or as few as you wish about the kind of care you would want in various end-of-life situations. … Third, regardless of where you are and when a need arises to make a decision, this document ensures you that someone you want will be the one making the decision ... Finally, opting for this document requires you to sit down with those who will have authority to make decisions for you and to discuss very clearly and specifically the kind of care you do or do not want in a crisis situation. … Using durable power of attorney gives you much more assurance than a living will does that the person making decisions for you knows what you really want and can be trusted to carry out your wishes.” Feinberg, 217-8.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beckwith, Francis J. and Norman L. Geisler. “Questions about Infanticide,” and “Questions about Adult Euthanasia.” In Matters of Life and Death: Calm Answers to Tough Questions about Abortion and Euthanasia, 131-163. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1991.

Bioethics, Issue Group. “Bioethics: Obstacle or Opportunity for the Gospel?” In 2004 Forum Occasional Papers, ed. David Claydon. Pattaya, Thailand: Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization, 2004.

Dunlop, John T. “A Good Death.” Ethics & Medicine: An International Journal of Bioethics 23 no. 2 (2007). Reproduced as “A Good Death,” 20 Jul. 2007. End of Life. Deerfield, IL: The Centre for Bioethics and Human Dignity, Trinity International University, n.d. https://cbhd.org/content/good-death (accessed Dec. 2014).

Elliot, J. M. “Brain Death.” Trauma 5, no. 1 (2003): 23-42.

Essex, Keith H. “Euthanasia.” Master’s Seminary Journal 11, no. 2 (2000): 191-212. http://www.tms.edu/tmsj/tmsj11j.pdf (accessed 19 Dec. 2014).

Feinberg, John S. and Paul D. Feinberg. “Moral Decision Making and the Christian,” and “Euthanasia.” In Ethics for a Brave New World. 2d ed., 21-62; 157-225. Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2010. Kindle.

Fowler, Richard A. and H. Wayne House. “The Respect for Life in a Permissive Society,” and “When Do We Pull the Plug?” In Civilization in Crisis: A Christian Response to Homosexuality, Feminism, Euthanasia, and Abortion. 2d ed., 59-65; 101-107. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1988.

Kaan, Terry. “Shifting Landscapes: Law and the End of Life in Singapore.” In Singapore's Ageing Population: Managing Healthcare and End-of-Life Decisions, ed. Chan Wing Cheong, 137-159 (selected pages). Routledge Contemporary Southeast Asia Series. New York: Routledge, 2011. https://books.google.com.sg/

books?id=5GarAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA137 (accessed 16 Dec. 2014)

Kehl, Karen A. “Moving Toward Peace: An Analysis of the Concept of Good Death.” American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 23, no. 4 (2006): 277-286.

Legislative Division. “Advance Medical Directive Act (Chapter 4A).” Singapore Statutes Online. Singapore: Attorney-General’s Chambers of Singapore, 2014. http://statutes.agc.gov.sg/aol/search/display/view.w3p;page=0;query=DocId%3Ac3137d32-215d-4bd1-a935-fc4770fc5850%20Depth%3A0%20Status%3Ainforce;rec=0 (accessed 22 Dec. 2014).

Ministry of Health. “Advance Medical Directive Act.” Legislation And Guidelines. Singapore: Ministry of Health, 2014. https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/ home/legislation/legislation_and_guidelines/advance_medical_directiveact.html (accessed 16 Dec. 2014).

National Council of Churches of Singapore. “Euthanasia.” Official Statement, 6 Nov. 2008. http://info.ncss.org.sg/joom837/index.php/m-statements/22-s10 (accessed 5 Dec. 2014).

Ramsey, Paul. “The Indignity Of ‘Death with Dignity.’” In On Moral Medicine: Theological Perspectives in Medical Ethics, ed. Stephen E. Lammers, 209-222. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998.

Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Translated by the author. “Declaration on Euthanasia.” Acta Apostolicae Sedis 72, no. 1 (1980): 542-552. http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_19800505_euthanasia_en.html (accessed 16 Dec. 2014).

Singer, Peter. “Is the Sanctity of Life Ethic Terminally Ill?” In Bioethics: An Anthology, ed. Helga Kuhse and Peter Singer, 344-353. Oxford: Blackwell Publisher, 2006.

Tang, Alex. A Good Day to Die: A Christian Perspective on Mercy Killing. Singapore: Genesis Books, 2005, 1-133.

Volker, Deborah L. “Control and End-of-Life Care: Does Ethnicity Matter?” American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 22, no. 6 (2005): 442-446.

Wennberg, Robert N. Terminal Choices: Euthanasia, Suicide, and the Right to Die. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1989. http://books.google.com.sg/books?id=KeY0rJ2qStsC (accessed 1 Feb. 2015)

Wennberg, Robert N. “The Right to Life: Three Theories.” In Readings in Christian Ethics (Book 2): Issues and Applications, eds. David K. Clark and Robert V. Rakestraw, 36-45. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1995. https://books.google.com.sg/books?id=GJbX_C-XLywC (accessed 20 Dec. 2014).

Appendix A

01 Feb 2015